Today's special feature is part of the O Canada! Blogathon hosted by Speakeasy and Silver Screenings. Click on the banner above to read more about the legacy of motion pictures in the True North Strong and Free!

Hollywood's "golden age" of the Twenties, Thirties, and Forties never wanted for stories of adventure set in the rugged wilderness of the mighty Northwoods. Between An Acadian Elopement in 1907 and the 1975 publication of Canadian historian Pierre Burton's damning Hollywood's Canada: The Americanization of Our National Image, 575 films were produced featuring mountainous and snowy locales populated by trappers, loggers and the women of disrepute who loved them. More than half of these, over 250, focused on that most iconic figure of Canadian history, the Mountie.

|

| CANADA! |

150 years young this year, the Dominion of Canada was negotiated into existence in 1867 through the Confederation of the disparate, independent British colonies of Upper Canada (now Ontario), Lower Canada (now Quebec), Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. In 1870, this new Dominion purchased the lands of the venerable Hudson's Bay Company, a then-200 year old fur trading monopoly that spanned the Hudson's Bay watershed. That truly immense holding stretched the four million square kilometres from northern Ontario to the Canadian Rocky Mountains. A year later, the independent colony of British Columbia opted to join Confederation on the promise of a railway connecting them to the markets in eastern Canada. In between was the vast, sun-baked, frost-chilled, expanse of forest and prairie purchased from the HBC, dubbed the Northwest Territories.

The North West Mounted Police were created in 1873 in response to a growing crisis on these prairies. The Indigenous peoples of the plains, whose traditional territory now overlapped with those of Canada, were in sharp decline. The demand for thick buffalo hides in New England drove American whiskey traders travelling up the Missouri River. Alcoholism, privation, and social disorder were introduced to the Indigenous peoples, culminating in the Cypress Hills Massacre of 1873. A group of American wolf-hunters pursued stolen horses into the Cypress Hills area and into a misunderstanding with a camp of Assiniboine, who the wolf-hunters promptly butchered. Such loss of life and violations of national sovereignty were unconscionable to the new Government of Canada. A mounted constabulary force was assembled to pacify the West, draped in the scarlet tunics of the British military (and in sharp contrast to the blue coats of the American Cavalry).

|

| The NWMP mustering on the barracks parade ground. |

A disastrous "Great March" brought them west in 1874. The NWMP were woefully unprepared for the harshness of the Canadian prairies. Black water could not slake their thirst, black clouds of mosquitoes tormented them, horses fell sick and died, men grew malnourished and exhausted, a trail of equipment was left in their wake, and they got lost along the way. Nevertheless, the NWMP eventually arrived at the main whiskey trader outpost Fort Whoop-Up to find it empty. Word was out that the law was coming, and the miscreants slinked back across the border. Thereafter, it was up to the Mounties to sign treaties with the Indigenous peoples, build forts, and ensure the proper, orderly, distinctively Canadian settlement of the West.

"Our Mounties were really civil servants and social workers," writes Pierre Burton in Why We Act Like Canadians, "enforcing the blue laws, succouring the sick, feeding starving Indians, settling domestic disputes, putting out prairie fires, collecting taxes, rounding up stray cattle, and taking off behind dog sleds or on horseback on endless patrols through wild, empty country." Author Ralph Connor once described them to an incredulous Teddy Roosevelt as "dry nurses to the community. They are everybody's friend. They look after the sick, they rescue men from blizzards, they pack in supplies to people in need." The Roughrider was convinced by pulpy, melodramatic novels that the Mounted Police drew their guns at the slightest provocation in a bloody and lawless Canadian frontier. In 1919, their jurisdiction was extended to the entire country, whereupon they were rechristened the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

"Our Mounties were really civil servants and social workers," writes Pierre Burton in Why We Act Like Canadians, "enforcing the blue laws, succouring the sick, feeding starving Indians, settling domestic disputes, putting out prairie fires, collecting taxes, rounding up stray cattle, and taking off behind dog sleds or on horseback on endless patrols through wild, empty country." Author Ralph Connor once described them to an incredulous Teddy Roosevelt as "dry nurses to the community. They are everybody's friend. They look after the sick, they rescue men from blizzards, they pack in supplies to people in need." The Roughrider was convinced by pulpy, melodramatic novels that the Mounted Police drew their guns at the slightest provocation in a bloody and lawless Canadian frontier. In 1919, their jurisdiction was extended to the entire country, whereupon they were rechristened the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

The picturesque qualities of the northwoods and its scarlet-clad riders were appealing to Hollywood, offering an affordable deviation from the cheap Westerns being produced in multitudes. The Interwar years were the heyday of these Wild West potboilers, being popular and easy to make. All a studio needed was to saddle up a few horses, pull out the cowboy on contract and send him riding around Griffith Park or the Vasquez Rocks after the outlaws. These B-movie fillers suffered for their rapidity, and one does not get very far into oeuvre of Roy Rogers before recognizing the same plot threads, or sometimes even identical stories. The mix could be livened up with a transplant into the wild Northwest. With a change of coat and headgear, the Southwestern sheriff becomes the scarlet-clad Mountie in a plot that could be - and most likely was - pulled from an American Western with only a change in place name. With a change in place name comes a change in location. Hollywood producers could shift away from the dusty valleys surrounding Los Angeles and migrate up to the Sierra Nevadas, standing in for the Canadian Rocky Mountains.

|

| Hollywood Mounties on set. |

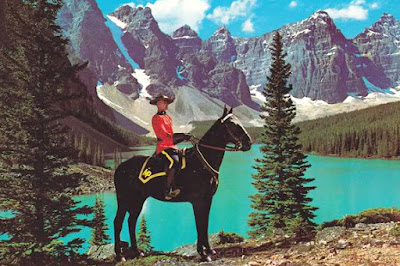

In most cases, this was considered good enough. The otherwise costly Rose Marie of 1936 was filmed in the Lake Tahoe region, doubling as an ersatz rural Quebec. A few were ambitious enough to actually film in Canada, like 1954's Saskatchewan. Unfortunately, the lavish technicolor backdrops of Banff National Park were about all the filmmakers chose to get right. The film features a great march from Fort Saskatchewan in central part of the province of Alberta to Fort Walsh in southwestern part of the province of Saskatchewan, which should be across open prairie and desert badlands. Instead, they traverse via Moraine Lake in the Canadian Rockies, over 500km west of either outpost.

|

| Hollywood's Saskatchewan. |

|

| Canada's Saskatchewan. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. |

One of the first successful "Northerns", as they came to be called, was Nomads of the North, based on a novel by James Oliver Curwood. He built an entire career spinning yarns about the "Great Northwoods" until his untimely death by spider bite in 1927 at the age of 49, becoming one of the most prolific and well-paid authors of the early 20th century. His 33 novels furnished plots for over 100 movies, many of which his own production company had a hand in creating. Though an American, the Canadian government furnished him with a stipend allowing him to spend 2-3 months of every year in the country, gathering materials for his stories. While the government had the intent of using his stories to help promote the nation, it was to the chagrin of the immigration office, who would have been just as happy to pay Curwood to stop writing about Canada. The problem was that Curwood was a writer of brisk adventure stories full of rape, torture, villainy and gunplay in the untamed frontier... The very impression given to Teddy Roosevelt and exactly the opposite of what the railways and land leasing agencies wanted to promote. Curwood's books were better suited to providing ripping melodrama for the silver screen than for encouraging immigration.

The first of Curwood's stories to be adapted to celluloid was in 1910, and while the pace has slowed it has never truly stopped. Nomads of the North released in 1920 by First National Pictures, starred Lon Chaney as the happy-go-lucky French Canadian fur trapper Raoul and Lewis Stone as stern Mounted Policeman O'Connor. These two suitors competed for the hand of the fair Nanette played by Betty Blythe, against each other and the slithering son of the cold-hearted chief of the Hudson's Bay Company fort (a chicken that would eventually come home to roost when the HBC finally sued Famous Players-Lasky for defamation in 1921, for its vicious, stock villain portrayal of the company in Call of the North).

Curwood's work supplied a good portion of the film vocabulary that would represent and petrify Canada as an exotic locale for an otherwise fairly standard American Western. We still have generic "Indians" living in tipis surrounded by totem poles, but instead of picturesquely ethnic Mexicans we have picturesquely ethnic French Canadians. Southwestern deserts are replaced by endless northern forests. Hudson's Bay Company traders frequently stand in for the monied interests, and Mounties take the place of sheriffs. While our Mounties are played considerably more straight-laced, they are still more free with letting the lead fly than they would be in real life. That and Hollywood never could quite get the uniform right. In Nomads of the North, Lewis Stone of The Lost World looks a little bit like he's a kid playing dress-up in his rumpled uniform.

Nomads of the North (1920)

Curwood's work supplied a good portion of the film vocabulary that would represent and petrify Canada as an exotic locale for an otherwise fairly standard American Western. We still have generic "Indians" living in tipis surrounded by totem poles, but instead of picturesquely ethnic Mexicans we have picturesquely ethnic French Canadians. Southwestern deserts are replaced by endless northern forests. Hudson's Bay Company traders frequently stand in for the monied interests, and Mounties take the place of sheriffs. While our Mounties are played considerably more straight-laced, they are still more free with letting the lead fly than they would be in real life. That and Hollywood never could quite get the uniform right. In Nomads of the North, Lewis Stone of The Lost World looks a little bit like he's a kid playing dress-up in his rumpled uniform.

|

| Lewis Stone in Nomads of the North, presumably on his way to summer camp with the Boy Scouts. |

Eight years after Nomads of the North, audiences were treated to two film adaptations of the stage musical Rose Marie. One of these versions starred a young Joan Crawford. The musical itself first took to the stage in 1924, featuring music by Rudolph Friml and Herbert Stothart and lyrics by Otto Harbach and Oscar Hammerstein II. The original version of Rose Marie was also the stage's longest running musical until it was surpassed by Show Boat. That musical about the lives and times of entertainers on the mighty Mississippi was first filmed in 1929, and both Show Boat and Rose Marie went head-to-head in 1936 with their iconic remakes. Both films were also redone in the Fifties as lavish, Technicolor productions: Rose Marie in 1956 and Show Boat in 1951. However, their 1936 versions are fondly remembered as true classic musical spectacles of Hollywood's golden age. Viewers have never forgotten the deep bass of Paul Robeson's "Old Man River" in Show Boat, or Nelson Eddy's swoon-inducing baritone "Indian Love Call" in Rose Marie.

Unsurprisingly, Hollywood's golden age coincided with the Great Depression. Through the Dirty Thirties, America was much in need of escape. Both Rose Marie and Show Boat are conspicuously timed to the metropolitan Thirties, at least for Show Boat's multi-generational ending and Rose Marie's opening and closing sequences. The bulk of each film, however, takes place in a bygone and archetypal age. Show Boat looks back to the era of king cotton and Mississippi riverboats. Rose Marie heads off into the Canadian backwoods populated by fur trappers and First Nations tribes. Both are caricatures meant to communicate the exotic in the visual vocabulary of cinema.

Caricatures serve their function, but do so at the expense of nuance and accuracy. For Rose Marie, not only could the filmmakers not settle on the geography (once again having filmed in the Sierra Nevada mountains), but they confused Indigenous tribes as well. The film placed the feather headdresses of the Plains people on chieftans surrounded by Pacific Northwest totem poles, all in northern Quebec. Our stalwart Mountie speaks with a New England accent, and like so many cinematic officers, was forced to choose between love and duty when his girlfriend's brother is wanted for murder, The girlfriend was, of course, played by Eddy's regular partner Jeanette MacDonald and her brother by a rising star named Jimmy Stewart.

|

| I don't blame her! |

Caricatures serve their function, but do so at the expense of nuance and accuracy. For Rose Marie, not only could the filmmakers not settle on the geography (once again having filmed in the Sierra Nevada mountains), but they confused Indigenous tribes as well. The film placed the feather headdresses of the Plains people on chieftans surrounded by Pacific Northwest totem poles, all in northern Quebec. Our stalwart Mountie speaks with a New England accent, and like so many cinematic officers, was forced to choose between love and duty when his girlfriend's brother is wanted for murder, The girlfriend was, of course, played by Eddy's regular partner Jeanette MacDonald and her brother by a rising star named Jimmy Stewart.

|

| It's not an easy job when Jeanette MacDonald is looking at you that way. |

Rose Marie was ostensibly the most successful of the Northerns, and so revolutionized the Hollywood Mountie. To be sure, the men in scarlet continued to get their man, but they began to do so with a song in their hearts. One of the archetypal of the Mounted Police heroes was Sergeant Douglas Renfrew, invented by Laurie York Erskine for a series of novels that ran from 1922 through 1941. Though a relative latecomer compared to James Oliver Curwood, Erskine's book Renfrew of the Royal Mounted, a radio show begun in 1936, and the eponymous 1937 film they spawned further cemented the image of Mountie as a pulp action hero.

|

| As unlikely a pose as could be adopted for a member of the Force. |

In the wake of Rose Marie, Renfrew had to become a singing Mountie, and the perfect actor was found in James Newill, coming hot off of his introductory role in Something to Sing About (1937). And like Rose Marie, Renfrew of the Royal Mounted wars time and space to create an archetypal image of Canada. Until the 1930's gangsters show up, one could just as easily think that the film takes place in a 19th century wilderness of trappers and loggers. The plot twist is the sort of thing that could only be credible in a Northwoods picture, and the climax has the man in red serge on his mighty steed chasing down tommygun-toting gangsters in classic sedans.

Renfrew of the Royal Mounted (1937)

Determined to create a "different type" of Mountie movie, Cecil B. DeMille released North West Mounted Police in 1940. It was based ostensibly on the North West Resistance of 1885, which was the closest that Canada has ever come to a civil war. That summer, a loose affiliation of aggrieved settlers, Indigenous peoples, and the Métis (an ethnic group descended from European men working in the fur trade and Indigenous women) took up arms in against the government. The rebellion was squashed fairly quickly by a well-armed expeditionary force of 5000 men (and 500 NWMP) supplied by the recently completed Canadian Pacific Railway.

In DeMille's hands, it took Gary Cooper as a Texas Ranger to lead them to victory, rather than the mere well-oiled machinery of British imperialism. In the climax, the Métis brandished a Gatling gun which, in historical fact, was employed by the Canadian military. Though claiming absolute historical realism, as was DeMille's hallmark claim from his Ten Commandments (1923) to his own remake The Ten Commandments (1956), he clearly played fast and loose with every possible historical detail. Even the central location of Batoche, on the high Saskatchewan prairie, was a stereotypical Northwoods setting. North West Mounted Police, besides injustices to Canadian history, is widely considered one of DeMille's worst films and even one of the worst films of all time. His deliberate attempts to stray from the B-movie formula ended up divesting the film of any redeeming value, even the enjoyment of kitschy Canucksploitation.

|

| Hollywood's Batoche |

|

| Canada's Batoche. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. |

The failure of the genre, however, suited the Mounted Police just fine. Bruce Carruthers, a former Mounted Policeman turned Hollywood consultant, once told of a director with the chutzpah to declare "Bruce, where would the mounted police be if it wasn't for motion pictures?" One can imagine the answer: doing our jobs. The Mounted Police never felt truly comfortable in the Hollywood machine, and typically kept it at arm's length. Their duty was and remains, first and foremost, to the peace and security of Canada. It was the commission of that responsibility, much more than Hollywood, that led the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to become revered Canadian icons.

3 comments:

Haha! I loved the question: Where would the Mounties be without motion pictures? Also, I burst out laughing at the photo of Moraine Lake posing as Saskatchewan. That really is a precious bit of creative license.

And, I loved your word "Canucksploitation".

This is a terrific post. Thank you for sharing all this research. I recently bought a used copy of Pierre Berton's "Hollywood's Canada", and now that I've read your essay, I need to dive into this book soon.

Thanks for joining the blogathon with this must-read post.

Thanks for having me! I enjoyed being a part and adding a new word to your lexicon! :)

Great post and overview of the Movie Mounties. So many approaches and genres, a few comical inaccuracies but yes, Canuckspoitlation is a fun area :) Thanks for taking part in this blogathon.

Post a Comment